SR U20s 2025

-

@Bovidae said in SR U20s 2025:

as the 1st half team tried to go wide at all costs and kicked poorly. The 2nd half team was more direct and got rewards.

I think it's more of a first five issue than a coaching issue per se. I like Rios Tasmania, he's a fun player to watch, but there's not a wide pass-option he won't go for. He'll need to learn to go for the more straightforward options as well.

As for Taumateine and Palmer, I didn't see them appear on the field either. Eti only played for 10 or so minutes in the second half, he appeared to have gone off with an injury. Hopefully nothing too serious.

-

-

@Mauss said in SR U20s 2025:

I think it's more of a first five issue than a coaching issue per se. I like Rios Tasmania, he's a fun player to watch, but there's not a wide pass-option he won't go for. He'll need to learn to go for the more straightforward options as well.

The starting 9-10 combo should be Farrant and Ticklepenny. Sinton to come off the bench at halfback.

-

Just seen a Hurricanes post saying they have the Chiefs this coming weekend, even though they played them last?

-

@Mauss said in SR U20s 2025:

@Bovidae I like the idea of an U23 competition. Having the U20 tournament is better than nothing of course, but it's more oriented towards NZ U20 selection (and even then, that's limited) than have any real benefit for player development.

-

NZ U20 preview: outside backs

What do the supposed NZ U20 outside-back crisis, Hurricanes attack coach Brad Cooper, the Brumbies’ increased ability to make metres and Josh Jacomb’s (relatively) poor form in 2025 all have in common? The missing link, in this particular instance, is attacking shape. While players are typically evaluated as individuals in relation to other individuals (RugbyPass’ new “head-to-head” stats feature a prime example of this) player’s ability and success is also highly impacted by such factors as system adaptability and dependency.Someone like Josh Jacomb, for example, has thrived in Taranaki’s attack system. When transplanted into a completely different attacking shape at the Chiefs, Jacomb is unable to immediately replicate these performances at the next level. Grabbing this particular premise, I wanted to look a bit closer at the NZ U20 outside backs between 2017 – the last time NZ backs like Will Jordan and Caleb Clarke truly dominated the tournament – to 2024, the period in-between typically viewed as an exceptionally fallow period for young NZ outside backs. I’ll try looking at some of the reasons for this lack of domination and reflect on what can be expected of the 2025 class.

Spotlight: The outside back-crisis?

It’s not an outlandish claim to suggest that the early success of the NZ U20s in the IRB Junior World Championships coincided with a rich vein of Kiwi outside back-talent. Players like Zac Guildford, Andre Taylor, Julian Savea, Telusa Veainu, Charles Piutau, and Beauden Barrett did not just win age grade championships, they terrorized opposition defences and put record scores on them. The same formula could be applied to the 2017 tournament, with Will Jordan, Caleb Clarke, Tima Fainga’anuku and Josh McKay scoring 16 tries combined across 5 games. That 2017 tournament was the final time, however, where the Kiwi outside backs were a genuinely dominant force, with both the overall try-scoring numbers as well as the outside back-try numbers heading in a strongly downward trajectory.

Figure 1: list of NZ U20s outside backs in their respective positions for the previous 5 U20 tournaments

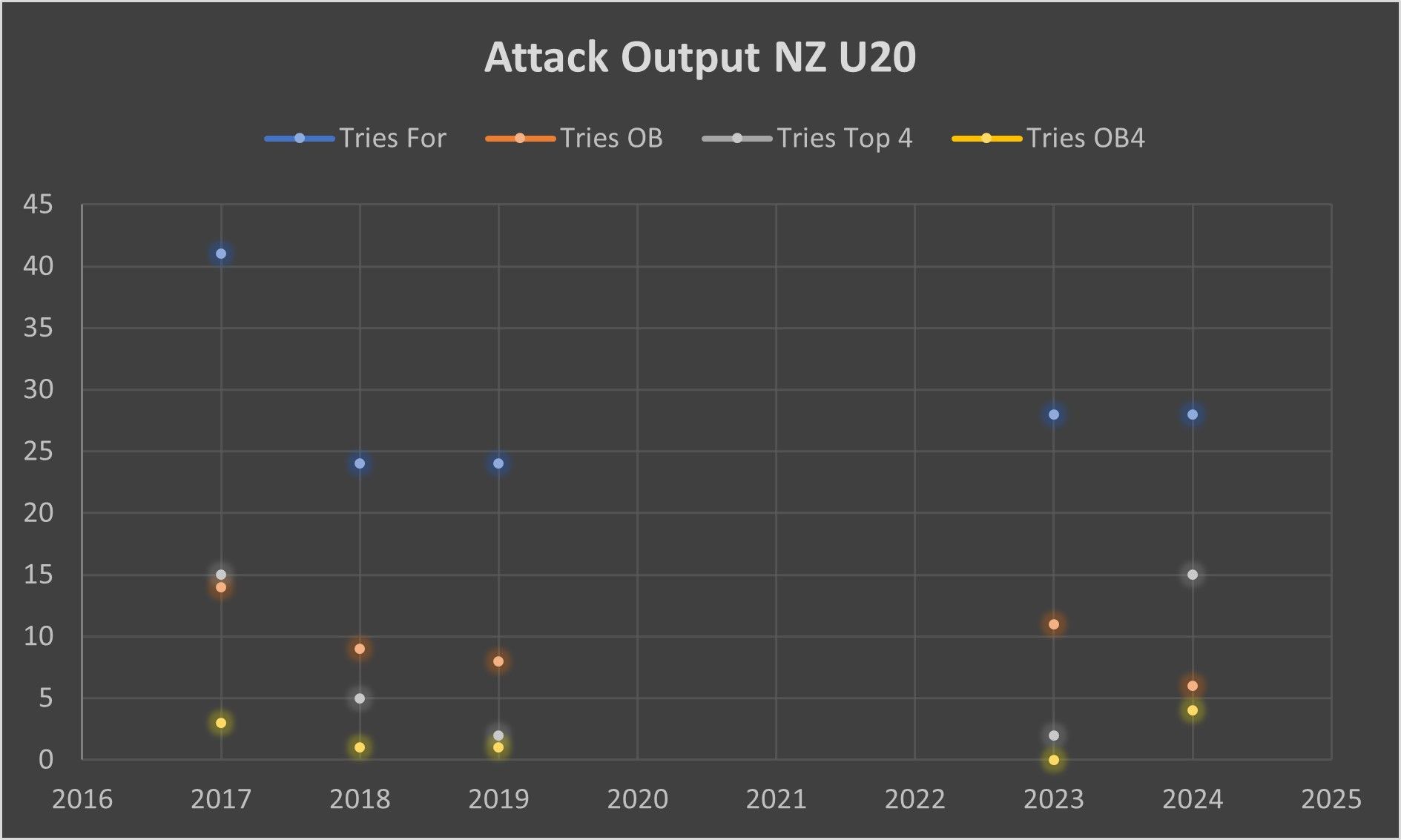

Figure 2: Try-scoring output (total and against top 4 opposition) and part of outside backs in output

Abbreviations:

OB: Outside backs

OB4: Tries scored by outside backs against top 4 oppositionSo what exactly happened since then? While our instincts quickly turn towards questioning individuals and their quality, I’d argue that, in this case, that isn’t a particularly useful perspective. If looking purely at individuals, the 2019 U20 outside back cohort is certainly above average. Leicester Fainga’anuku, Etene Nanai-Seturo and Cole Forbes form a complete back three and, furthermore, have already more than proved their qualities at the highest levels of the game. At age grade level, they had, together with Quinn Tupaea and Danny Toala for NZ Schools, annihilated the Australian Schools team in 2017, so the expectation was that they would repeat these feats at U20 level in 2019.

It would turn out very differently. First, they were kept to zero points in their game against Australia U20 at the 2019 Oceania tournament, many of their opponents the same players they had thoroughly beaten only two years earlier. Then, at the U20 World Championships in Argentina, they showed again that they had difficulties scoring in tight games, South Africa keeping them to only 17 points while Wales were able to limit them to just 7.

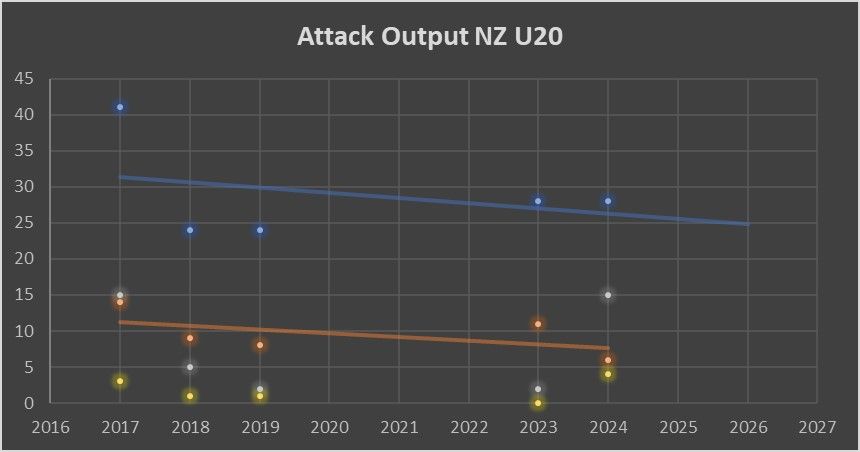

Looking at the numbers across these tournaments (2017-2024), this downward trend in scoring, both overall and for outside backs, is further made clear.

Figure 3: Graph display of fig. 2

Figure 4: linear trend for both overall try-scoring and outside back try-scoringThe argument that imposes itself is the one that has defined not just age grade rugby from 2017 onwards but the rugby world in general. Defences, at all levels, have improved markedly, making it harder to simply rely on superior athleticism and fitness in order to rack up large scorelines.

At the same time, however, attacking systems are evolving as well, continuously looking to match defensive innovations in this rugby systems-arms race. France, after winning their first two U20 World Championships on the back of their defence, amplified their attacking game in 2023, putting 50+ points on both their semi-final (England) and final (Ireland) opponents. Their dominance of the 2023 U20 World Championship mirrored the superiority of the NZ U20 teams between 2008 and ’11, where opponents weren’t just beaten but were plowed, headfirst, into the turf.

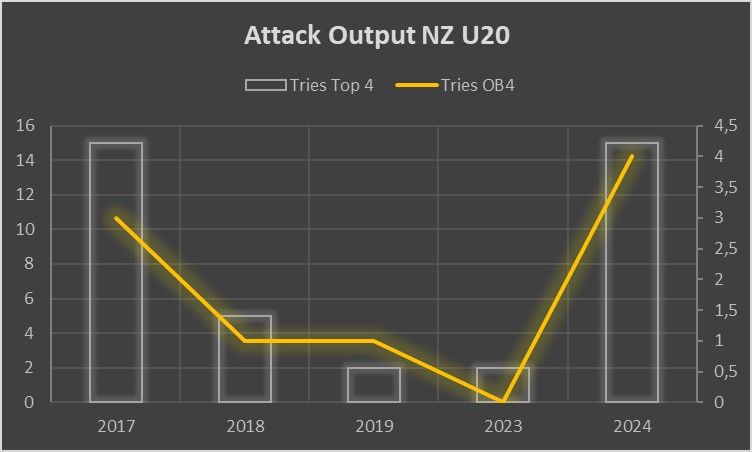

As far as New Zealand’s participation into this arms race, 2024 represented a first successful foray since 2017. While their 28 overall tries (see fig. 2) only just equalled the 2023 NZ U20 class, it was their success against top 4 opposition (typically the best defensive performers) which signalled the real improvement, rising from just 2 tries against this opposition in the previous year to a much-improved 15.

Figure 5: Try-scoring against top 4 teams in previous 5 U20 tournaments, both overall and outside backsLooking at the data from this perspective, the 2024 NZ U20 team were able to return to 2017 levels of scoring against elite opposition, with an even better rate of outside back-production against these teams. By contrast, 2018, ’19 and ’23 stick out like a sore thumb, with the team failing to crack the tournament’s toughest defences. So while the wingers supposedly had a good year in 2023 with 11 out of a total of 28 (fig. 2), the majority of these tries came against teams like Japan and Georgia, where large scores were racked up against relatively poor defences for this level.

Going vertical

So how were the NZ U20s able to put on these big scores against better defences? The main factor, I’d claim, would be their choice of attacking shape. Brad Cooper, the 2024 NZ U20 attack coach, prefers a stacked attacking shape, where attacking players line up in a vertical position behind each other. As the play unfolds in a certain direction, these stacked players typically run in looping lines inside the carrier’s shoulder, ‘hiding’ the attacking play from the defence. As Ben Smith, the controversial but technically excellent analyst from RugbyPass puts it in an article on the Exeter Chiefs’ attack from 2019, “[u]sing stacks is a way to create pre-play misalignment with defenders. It immediately forces the defence into ‘zone’ type coverage, where they have to decide which man to take on the run without knowing beforehand which man is theirs.” [https://www.rugbypass.com/news/analysis-the-exeter-chiefs-have-invented-rugbys-newest-attacking-structure-that-might-double-the-size-of-coaching-playbooks]Defences use the horizontal positioning of the attackers as a way of numbering up. When the attack has backline players constantly moving in loops, following the play across the field, this numbering exercise becomes substantially more difficult.

Someone like Cooper has tried to implement some of these vertical elements into his attacking gameplans, both for the Taranaki Bulls and the NZ U20s. The innovation here lies not so much with the attacking shape itself. Exeter Chiefs have used these shape formations for a number of years, as have several other teams in Europe, such as Leinster and Clermont. It’s not even something particularly unknown for high-level professional teams in New Zealand, as Super Rugby teams such as the Crusaders and Chiefs have integrated some of these formations into their attack while the ABs have also used parts of it in their 2024 set-piece attack.

What is innovative is the implementation of more structured attacking shapes at the lower, less professional levels of the game. The mantra at NZ age grade levels has, for a long time, been to let players play “heads up footy”, where they play a simple pod-structure in order to allow them to see what is possible in attack. A stacked, layered attack can be quite a departure from the regular 1-3-3-1 pod system which is typical in NZ Rugby, as it requires a lot of structure and coordination between the backs. For example, considerable teething issues were experienced by the Taranaki players when the attacking shape was first implemented by Cooper in 2023. Meihana Grindlay, the starting 13 in the 2023 Bulls side, relayed some of these issues in a 2024 interview: “Originally we were like, ‘What the heck is going on?’ We’re not used to playing like this, everyone plays a 1-3-3-1 pattern. After we lost to Ta$man we had a bit of an honesty session. We had to make it work. We did. We didn’t lose again.” [https://www.rugbypass.com/news/what-the-heck-is-going-on-how-irelands-style-helped-young-taranaki-centre-to-a-blues-contract/]

Taking a quick look at the Taranaki attack shows both the obvious benefits as well as the potential difficulties of the system. In the 2023 Bunnings NPC final, the opening score was a direct result of an double attacking loop, presenting the defence with too many options to handle.

Grindlay score

Taranaki attack with the double pod out the back. Jacomb uses the defence’s uncertainty to attack the line and offload for the Grindlay tryAnother advantage of the system is that it allows the attack to effectively make metres ball-in-hand, as looping players are arriving at the line with both pace and options outside of them. This solves a consistent issue within the 1-3-3-1-pod system, as a lack of quick ball at the ruck can mean that the players are already in place in attack but have to wait for the ball, making the defence’s job much easier. The looping players, on the other hand, are stacked on the inside of the ball carrier, meaning that they only move in their attacking positions when the ball is in play.

Taranaki players arriving at the line with paceSo much for the advantages, though. The benefit of the system doubles up as it’s Achilles’ heel as well, with the complexity experienced by the defence also being shared by the attackers. If there’s a lack of clarity of which option is going to be taken by the ball-carrier, there’s a high chance of a confused attacking shape and an increased risk for conceding turnovers. In the following instance, for example, Jacomb decides to take the ball into contact, hoping to offload with committed defenders. Chase Tiatia, however, has already detected what Jacomb is going to do and is moving into the space of the looping players. Jacomb still chucks the offload and, in this case, is lucky that the ball only drifts into touch.

Attacking confusion2024 NZ U20 attack

We can now take a look at the NZ U20 attack, focusing on their opening game against Wales at the 2024 World Rugby U20 Championships. While most teams go to these vertical pods in a set piece-context, the NZ U20s also implemented them in phase play as well, as this example around the 5 minute-mark shows. Pledger arrives at a ruck and Rico Simpson has called the shape and this is the picture:

Phase play example of vertical podsIt’s easy to see how this is challenging to defend from a Welsh perspective, a standard attacking triangle, with three looping players right in behind while Bason is running a decoy line towards the blindside. On the right edge, Matt Lowe, the number 7, is waiting to run a hard line against the grain when the play comes into his direction.

Lee, the tip of the triangle, throws the backdoor pass to Tuivailala, who now has another backdoor option (Simpson), with an extra looping player (Coles) and a player running a hard line (Lowe).

The Welsh 13, Hennessey, is now isolated, with multiple running options coming straight at him.In the end, the line-break is constructed with Lowe being put into the gap but the latter loses the ball as he’s trying to offload in contact.

Solid shape but iffy executionWhat is clear from this example is that this attack can only work if you have a back three which has (1) a big work-rate and (2) an ability to act as a secondary playmaker. Players like Sam Coles and Stanley Solomon might not be prototypical Kiwi outside backs – if we remember the likes of Savea, Piutau and Jordan who are extraordinary finishers – but they thrive in a system like this where they are constantly shadowing the play, looking for opportunities to put others into space.

Someone like Frank Vaenuku, a player more renowned for his physicality both in the tackle and the carry, showed great aptitude for playing in this system as well. Another example occurred in the 27th minute. From a lineout around the NZ 22, Pledger and Simpson get the ball to Lee who looks set for a typical midfield carry.

Another triangle, with Taele and Vaenuku as two ‘stacks’ looping aroundInstead, the ball goes out the back to Taele who steps inside his man before passing again to an overloading Vaenuku, who takes the ball at pace before releasing Coles. The Welsh line is easily broken and the play ends up deep into the Welsh 22 with Solomon at the end of the chain.

Notice the not so subtle blocking line by Lowe on HennesseyThe presence of the second ‘stack’ is crucial, both as a potential passing-option as well as a decoy. The defence needs to take someone like Vaenuku looping around into account, making it much more difficult to execute solid defensive stops through early defensive reads and double tackles. Instead, a stacked attack can fracture a defence by constructing one-on-one match-ups, the looping players giving the attackers continuous options in order to take on the next defensive wave.

In a final example, we can see the value in having a kicker like Stanley Solomon on the wing, as the double pods out the back creates time and space for the wing, which can use it to kick behind the opposition defence and put them under further pressure. Again, from a lineout around the NZ 22, Pledger and Simpson combine to put the ball in midfield. Again, Lee passes out the back to Taele.

Similar shapes, different decisionsNow, however, Vaenuku serves purely as a decoy, the defence remembering the stacked attack from the first half. This double pod out the back-system allows for multiple options, however, with several players running at pace at the same time, making it, again, very difficult for a defence to pinpoint where the attack is going to go. In this instance, Taele goes wide to Tuivailala who passes quickly to Coles. Now Coles has plenty of time and space which he uses to pass quickly to Solomon who is able to kick behind the defence without any pressure whatsoever.

Turning a stacked attack into territorial pressureThe NZ U20s end up turning the ball over around the Welsh 22, leading to a score in the corner for Taele. The benefit of this attacking shape, in other words, is not just its ability to create finishing plays but to construct territorial pressure as well, allowing the NZ U20s to play in the right areas of the field without resorting to endless kicking.

Is there an outside-back crisis?

The lack of Kiwi outside back-dominance at U20 level since 2017 could be interpreted in many different ways. While it’s certainly true that there hasn’t been a power-athlete like Julian Savea or Caleb Clarke in the past few years, the question also remains whether they would be as dominant as they were in the 2010s, with defences out wide improving markedly, even at U20 level. What does appear certain is that the NZ U20 attack was struggling to break down the defence of the best teams in the competition between the years of 2018-2023, even through such talented players like Leicester Fainga’anuku and Etene Nanai-Seturo.It was only with a new tactical impetus, under the guidance of 2024 attack coach Brad Cooper, that the outside back try-scoring rate of 2017 could be restored. It shows the importance of tactical innovation and structure in the game, even at age grade level, where playing “heads up footy” is becoming more and more difficult in the face of rigorously-trained defences. And while it does appear that there will be a lack of outside backs with an exceptional athletic profile for at least the next few years (with only someone like Siale Pahulu from St. Kents really fitting that mould in my personal view), the recent changes do indicate an evolution for the Kiwi outside back, one where they are expected to be more tactically and technically astute.

The NZ age grade wingers of 2025 might not be as offensively game-breaking on an individual level as they once were but they are evolving in the same way that the game as a whole is evolving. Someone like Nathan Salmon, for example, isn’t very likely to run through an entire opposition defence, his John Kirwanesque appearance notwithstanding. But, much like his fellow wing Frank Vaenuku, Salmon is an exceptional defender, both in his ability to make defensive reads as in his ability to execute his tackles.

Salmon putting the complete in completed tackle Excellent defensive drift and pressureOther eligible outside backs, like Solomon, Xavier Tito-Harris and Maloni Kunawave, are excellent secondary playmakers with great skill and pace, who’d be very handy (and have already showed so) in an attacking shape like Cooper’s. So would've been someone like Kiseki Fifita, you’d imagine, but he’s still a few years removed from professional rugby due to his missionary work. Others, like the Highlanders’ Josh Augustine and Kyan Rangitutia, will look to make their mark at the U20 tournament, in their bids to make the squad. The prototype of the age grade Kiwi back three is slowly breaking up, which means that there are opportunities for new players and new types of players to stake their claims.

-

@Mauss super interesting and makes a ton of sense. The game and game plans are evolving and whilst its harder to find a Savea, Clark or someone of that ilk, it may not be nessessary or a requirement anymore to always have that power winger.

If you dont mind me asking Mauss, what do you do?

You sound like a coach or tech advisor for a team. Id put money on it.

-

There hasn't been a lot of continuity in the NZ U20 coaching group in recent years compared to those early days. That hasn't helped if the systems change from one year to the next. While Jono Gibbes won't be involved in 2025 hopefully Brad Cooper is still there.

-

@Left-Right-Out-0 said in SR U20s 2025:

If you dont mind me asking Mauss, what do you do?

No worries. Nothing in rugby, I can tell you that

. Just enjoy watching and writing about the game.

. Just enjoy watching and writing about the game. -

@Bovidae said in SR U20s 2025:

While Jono Gibbes won't be involved in 2025 hopefully Brad Cooper is still there.

There's been a lot less communication about the coaching group and even player camps this year, I feel. It'd be great for Cooper and Hoeata to continue in their roles, I thought both the attack and the forwards went quite well last year.

-

Is there a NZ U20 squad being selected from this U20 super comp?

-

@Bovidae canterbury were great to watch. That pack and with the young 10 pulling the strings, no doubt favourites for the comp in a couple weeks time.

To be honest, that video doesnt quite show just how dominant their forwards were. Some poor tackling by Wellington in their pack and at 1st 5 made for a long day. Outside backs look the goods though.

-

@Bovidae Some interesting things to note from the Crusaders U20s, even from those short highlights. That looks to be Finn McLeod who was playing at number eight, who is usually a lock/6. 8 might suit him though, watching him during the Global Youth Sevens it was apparent that he has a great skillset. It might be just a temporary switch – I didn’t see Saumaki Saumaki anywhere, who might be expected to play there – but I do think McLeod has the potential to make a very complete 8.

Another position shift looks to be James Cameron moving to inside centre. He did play some games at 12 for Westlake Boys I think, but he typically played at 13. Could be an interesting move, as I can’t really recall any clear stand-out candidates at 12 for the NZ U20s. His combination with both Inch at 10 and Cooper Roberts at 13 could be a very solid midfield-axis.

Also good to see some dominance at the scrum from Tonga Helu and Sione Mafi, as both have struggled there in the past. The only caveat is that I don’t think the Hurricanes U20 scrum is particularly good, so it’ll be interesting to see whether they are as dominant against the other teams.